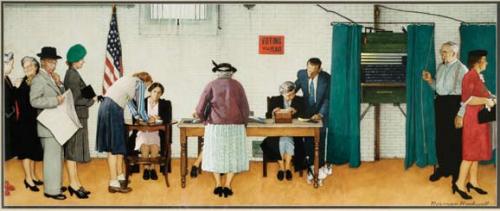

Voting – my Norman Rockwell moment 5

By Lisa Dale Jones

When I moved from Boston to Ambridge, Pennsylvania in 1992, I knew nothing about it, other than its proximity to Pittsburgh – where I expected to find a job. I stayed with a friend in upscale Sewickley while looking for a place to live, so it was natural to look along that part of the Ohio River. Ambridge, with its supply of small houses with low rental rates, seemed perfect.

I found a house, probably built in the 1940s and not changed since, with two bedrooms, three bathrooms, living room, dining room, den, eat-in kitchen, and unfinished basement – all for $400 per month. When I asked the landlady about the toilet, sink, and shower sitting out in the open in the basement, she said that steel mill workers would come home from work filthy, and go right into the house through the bulkhead door, wash up in that expansive basement bathroom, and then come upstairs to the house nice and clean.

Of course, the steel mill that gave the town its name was gone. Ambridge was named for the American Bridge Company, previously one of the largest steel companies in the country. Now, the town had a large population of retirees. Anyone of working age had left to find jobs elsewhere – something I didn’t know when I moved in.

The landlady, who lived elsewhere, told me that if anything “needs fixed” to call on the handyman neighbor across the street. He was retired from the railroad, liked to putter, and was happy to come over and work on things. The first time I went to his house, his wife showed me her salt and pepper shaker collection. It filled every open space in the living room and dining room. The handyman himself had clearly been a deer hunter for many years. Around the top of the walls were twenty taxidermy deer heads. At the end of the line was a plaque with deer paws. He explained that he had run out of room for the heads, and was now only putting up one paw for every deer he shot, until that plaque would also run out of room. He, and everyone else in Ambridge who hunted deer, had large freezers in their basements filled with venison.

Most of my neighbors were like the handyman: older former steel workers and railroad workers, with central European roots. The Serbian Club was at one end of Main Street and the Croatian Club at the other. The busiest restaurant was Polish.

I began to realize how odd I was to “Bridgers” when I first mowed the lawn. My house, like everything else in Ambridge, was on a hill, and the front lawn had a slight slope, until a few feet from the sidewalk it became almost vertical. The landlady provided me with a lightweight electric mower with a strong rope tied around the handle. I was to lower the mower down the six-foot slope with the rope and then haul it back up a little bit over, repeating all the way around until the vertical was mowed. The first time I tried this, with questionable success, I noticed some curtains across the street moving, and in more than one house. I could only imagine the phone calls going from neighbor to neighbor…

“Wilma, do you see that young woman from out east? She’s mowing the lawn. Yes, she lives by herself. But she has rich friends!”

It’s true. My friend in Sewickley worked for a Porsche dealership and would leave a different $90,000 car parked out front each time when making the occasional visit. And for a while I dated a man who drove a classic MG sports car, which was duly parked in front for everyone to ogle. Even my little Toyota Corolla stood out as the only Japanese car in town. I was clearly fodder for the gossip mill.

I registered to vote as soon as I moved to town in August. The town hall had no computers, so the town clerk had me fill out a card, which she then filed in a wooden box suspiciously like a recipe file. This was the same method used to sign me up for trash pickup.

Election day came. Bill Clinton was running for President against George H. W. Bush. I walked down the street a few blocks to the church whose basement was the local polling station. As I opened the door there was a buzz of conversation going on as people got their ballots and were shown to the polling booths. Suddenly all noise stopped. Everyone was looking at me. As if I was the gunslinger pushing open the double doors in a western saloon and interrupting normal daily life.

Finally, one of the poll workers said, “You must be new here.” I nodded yes. She brought me over to the check-in table where I stated my address and was handed a paper ballot. As I stood in the curtained booth voting, I heard the poll workers start to talk about my next-door neighbors. This one’s granddaughter had just graduated from high school. Another one’s mother had just died. Another one had gotten a new car. Someone else was working on his furnace. And so it went, the entire time I stood in the booth voting. Everyone knew something about everyone else. As I cast my vote for a president to govern the entire country, I was firmly enmeshed in small-town democracy – replicated in thousands of polling places across the USA.

I lived in Ambridge a little over a year and got to know a few of my neighbors, although I’m sure they regarded me as a transplanted exotic. Fulltime work in Pittsburgh eluded me, and I eventually returned to my old employer in Boston.

Today I live in Washington, DC. On Tuesday, I’ll walk to my polling place past the US Capitol, the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court. When I walk in, whatever conversation was happening…will continue. I’ll vote on an electronic voting machine, and be given an “I voted” sticker by a friendly poll worker who has no idea who my neighbors are. This, too, is democracy – city-dwellers voting in relative anonymity near landmarks and office buildings – replicated in thousands of polling places across the USA.

the Supreme Court. When I walk in, whatever conversation was happening…will continue. I’ll vote on an electronic voting machine, and be given an “I voted” sticker by a friendly poll worker who has no idea who my neighbors are. This, too, is democracy – city-dwellers voting in relative anonymity near landmarks and office buildings – replicated in thousands of polling places across the USA.

Since turning eighteen I’ve voted in fire stations, church basements, elementary school cafeterias, and retirement home recreation rooms. The poll workers have been Russian immigrants, African American retirees, volunteer librarians, and even my grandfather, proudly wearing a Panama hat and a western bolo string tie over his favorite polo shirt. It’s the polling places and the poll workers who have my vote. Every two years, they proudly invite the rest of us to participate in democracy – whether we’re in a small town, large city, or something in between.

There are a few Norman Rockwell-type events that get to me. One is stopping for school buses. When I see cars halted for the flashing lights on a school bus so children can cross the street, I get a lump in my throat to observe drivers doing what’s right so children can be safe. And I get that same lump in my throat when I show up at a polling station and see lines of people waiting to exercise their sacred right to vote. The more diverse the people in line, the prouder I am of my country. And I’m always grateful for the poll workers. Those poll workers, whether in large cities or small towns, are our ushers to the ballot box. Nothing pleases me more when one of them gives me a sticker that says “I voted.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

November 11, 2014 @ 5:16 pm

Well, Lisa, I missed my opportunity to share it in 2014! Reading it was like it was brand new. Thanks for sharing, amiga.

November 20, 2012 @ 1:51 pm

I’m a little late finding this post, so I’m not sharing it with FB friends. Maybe in 2014? So well written. Makes me all throat-lumpy.

November 8, 2012 @ 5:04 am

fun article…

and one could “wonder” considering how all your furniture and boxes got to that PA residence?…:-)…

am sure it was an Adventure – no matter how!…

November 10, 2012 @ 10:17 am

Thanks for your moving services!!

November 4, 2012 @ 9:06 am

Lisa, great article. , and yes, I was in tears,,especially when I read about your grandfather wearing his bolo tie and Panama hat on voting day! He was so proud to be an American and to vote. (and I have that bolo, and that amazing man was my father.) Mom